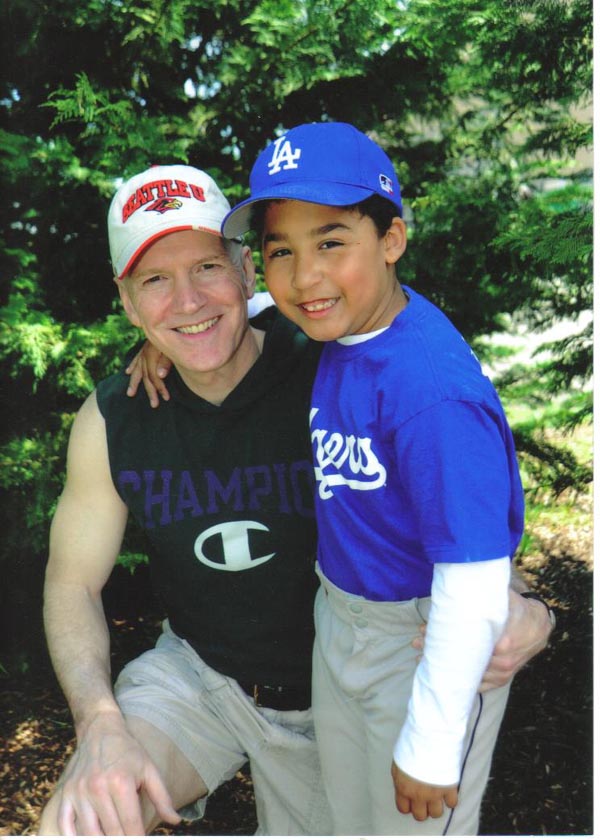

CLAY MOYLE AND SON CALEB

BENNETT HARTON MOYLE

By Clay Moyle

My 82-year-old father, Bennett Harton Moyle, passed away on February 23 as a result of complications from a major stroke suffered on February 10. Dad loved sports all his life and he instilled that love in each of his children. When my brothers and I were born he painted a number of murals of football players on our bedroom walls. He was a talented amateur artist and those murals were quite beautiful.

Ironically, the Moyle children ended up focusing more on basketball than any other sport and after spending the past six months trying to recover from a bad concussion as a result of a fall off a ladder I have to say I’m not sorry I didn’t pursue football.

On the occasion of my father’s 70th birthday, I took the opportunity to write him a letter and tell him how much I loved him. In that letter I told him how much of a sports hero he was to me when I was a young boy because his athletic exploits seemed larger than life to me at the time.

In my ignorance, I remember asking him in wonder at the time why he hadn’t played professionally. I’m sure it wasn’t that long afterward before I realized he didn’t possess that level of athleticism.

Despite the athletic limitations I would eventually come to realize my father could run like the wind. As a young man he once received a new stopwatch as a gift and he was so eager to use it that he had my grandfather accompany him to a local track. On a wet track and without the advantage of any starting blocks or track shoes he ran the 100-yard dash in just a shade over 10 seconds. On top of that natural speed it seemed to me as though he could throw and hit a baseball much further than I could imagine at that time.

But, dad was born with something called a lazy eye, a condition that causes the brain to favor one eye due to poor vision in the other. When I looked the condition up I learned that the brain often eventually ignores the signals it receives from the weaker or so-called lazy eye. As a result, he essentially went through life with one eye.

I recently asked him if just how much he could see out of the poor eye and he told me he was able to make out movements peripherally and then turn his head in that direction to see out of his good eye but he didn’t otherwise get much use of the bad eye.

So, that obviously hindered dad’s own athletic endeavors. He was also a late bloomer and didn’t really begin to come into his own athletically until he’d finished high school. But that didn’t prevent his love of sports in any way and he eagerly joined any pickup game he came across as a younger man.

I’m sure he couldn’t wait to get his own kids involved in sports. There’s a home movie somewhere that shows me shooting baskets as a toddler on a makeshift hoop he put up in our basement, and I can recall a number of early photos of my brother and I dressed up in various athletic gear around that time as well.

Dad was that guy who would round up all the neighborhood kids in the evenings or on the weekend and haul us all over to the local ball field where he would hit us endless fly balls, grounders and teach us all how to hit.

The other adults in our Queen Anne Hill neighborhood must have thought he was absolutely nuts when he nailed four long unpainted two-by-fours across their large bedroom window to prevent it from being broken by any errant shots on a hoop he put up just below.

By the time I was eight dad began dispersing various athletic pearls of wisdom to me. I remember the first time he taught me how to dribble a basketball and shoot lay-ins that he stressed the need to be able to do both equally well with either hand. It was the kind of advice I took to heart and practiced diligently to make him proud.

He also told me that no matter how good you got there was always somebody out there better and that one needed to continually practice to become as good as possible.

If you were willing, dad was happy to be there to help you get better. He put in countless hours hitting me fly balls, playing catch, rebounding shots, and helping me work on the fundamentals and I loved every minute.

When we got a bit older and moved to Bainbridge Island he put in a cement basketball court for us in the backyard and hung a huge light off the corner of the house so we could play ball at all hours of the day. That little court got more use than you could possibly imagine, and the neighbors would occasionally remark about hearing the pounding of the basketball into the night.

All five of us went on to play varsity basketball at Bainbridge Island High School as well as a few other sports along the way. Dad never missed a game if could help it, and that really never changed.

Later in life, he always attended an awful lot of my men’s league recreational basketball games, and there were many times he’d be the only parent you’d see sitting on the sidelines watching his children play during open gym. As a former teammate recently remarked, dad was always in our corner.

When all his kids were out of the house and dad was nearing retirement he turned his attention to coaching team basketball. He started purchasing instructional videos and was always anxious to show me the latest one whenever I visited.

He was always looking for ways to improve athletic performance. I remember there was one day I visited when he pulled out some video or article on improving one’s vertical leap. I had to laugh as I reminded him that I was in my early 40’s and didn’t think there was much hope at that point.

But, a lot of dad rubbed off on me. The fact that I developed a fanatical life-long workout habit and continually worked on my game allowed me to continue competing at basketball against much younger men a lot longer than I ever imagined I would.

Dad went on to become a darn good basketball coach for a number of middle school and high school teams, along with many of his grandchildren’s youth league teams over the next 25 years. He loved teaching the kids the fundamentals of the game and a many youngsters reaped the benefits of his coaching.

But as much as he loved sports, dad was about so much more and that’s the reason that although I eventually came to realize his athletic limitations he remained my life-long hero. He was a hero to me for the things that really matter in life.

Dad was possibly the most selfless individual I’ve ever met. He was always looking to do for others. As my brother Curt said, you had to be very careful about saying anything about something you needed to get done, or anything you needed to purchase, because the next thing you knew dad had taken care of it for you.

He was just that kind of guy. I can’t tell you how many times I came home to discover he’d come over earlier in the day and done something for me, or I found something he’d purchased for us sitting on the porch. We really did have to be careful what we shared with him.

A few days before he suffered the stroke, I was watching a ballgame with him and he asked me if he didn’t need to organize a work party to tackle a number of projects I’d put on the backburner at my home while recovering from a concussion.

Never mind that he was 82-years-old, had a torn bicep and two torn rotator cuffs that he’d never had repaired, and his legs had been bothering him of late. It took a lot more than that to slow him down. I had to tell him I had it under control while making sure not to divulge any information about those projects.

Dad worked hard his entire life. He’d put in a full week at his warehouse job only to spend many of his weekends doing odd jobs to help make ends meet. And if he wasn’t getting paid for that type of work, his weekends we’re typically occupied putting on a new roof, painting a house, repairing something, or moving something very heavy for one of many older family members in the area.

I would sometimes get annoyed that he was the guy everyone called to do that kind of work to his dying day. But dad never seemed to mind in the least. He was one of the most generous and cheerful guys you could ever hope to meet. He seemingly just loved to help people.

My brothers, I would often accompany him on a lot of this work and we eventually came to call them work parties. It wasn’t unusual to get a phone call a day or two in advance advising that there would be a work party to do this or that for someone that coming weekend.

While the activity itself generally wasn’t something that sounded like much fun, the fact that you’d be spending time with my father and most likely one or more of your brothers always was. We always had a ball with one another joking, sharing stories, laughing and hurling insults at one another during the day regardless of how hard the work was.

Dad remained active his entire life and you just couldn’t keep him down. At his memorial service, I shared a story about how disgusted he’d been just a few days after having a pacemaker installed at age 74and that it has been so difficult for him to move a refrigerator in their kitchen all by himself.

While he never minded doing for others, he was always trying to do something on his own without asking for help himself. My mother eventually became pretty good at alerting myself or one of my brothers when she knew dad was going to tackle something along those lines.

But he soon caught on and became more secretive about his plans. Sometimes she would call us after he’d already started so we could try and race over and help out. But he’d often just wait until nobody was around the house to tackle it.

He also always got a lot of pleasure working with kids and was still very active in coaching.

Less than a month after my accident (a fall off a ladder), he and I took my son Caleb over to a local schoolyard to work on post moves. I was suffering so badly from my concussion that my father took the lead and proceeded to demonstrate a move he wanted Caleb to master.

He began by showing him how he wanted to make himself big for the entry pass. Then he showed him how he wanted him to take one big dribble to wheel into the center of the key, drop down and then explode up toward the hoop.

It was the moment that my father dipped down low that he went crashing over on his side to the asphalt. The possibility of a broken hip flashed through my mind, but luckily it was just another of many bruises to add to his collection.

But, it was clear that it was becoming much more difficult for him to demonstrate basketball moves. It was already a problem showing the boys how to shoot because his shoulders were so bad that he could barely lift them over his head.

But that didn’t stop him from trying. In fact, he was still working with the local boy’s 7th grade basketball team just prior to his death in what he said would be his last season of coaching.

He’d already invested quite a bit of time in teaching my son many of his favorite low post moves and I always got a big kick out of witnessing any of his pupils successfully pull off one of those maneuvers in an actual game over the years.

Dad also had as much integrity as anyone I ever came across. If he said he was going to do something, or be somewhere by a specific time you could put it down in stone. His word was his bond. He priorities in life were always perfectly clear: God, and caring for family and friends.

Dad had accepted the Lord as his savior as a young boy and he was a dedicated witness to his faith his entire life. He was our spiritual leader and I don’t know that he could have been a better role model in that regard.

He loved nothing better than spending time with family and friends. He had a terrific sense of humor, boundless energy, and was always so cheerful and fun to be around that you just couldn’t help but enjoy yourself.

When my siblings and I had started our own families, my folks loved nothing better than an opportunity to go away with us for a weekend each summer to spend time with one another playing games and enjoying one another’s company.

Whenever that occurred you could be sure dad would set aside some time to deliver a spiritual message at some point. It was his greatest wish that his entire family would come to know the Lord as he had and we would all one day be reunited in His presence.

Retired NBA great Charles Barkley once made headlines in 1993 for a television commercial in which he said, “I’m not a role model. Just because I dunk a basketball doesn’t mean I should raise your kids.”

Unfortunately, too many kids look up to professional athletes, though, and too often select the wrong kind of example to emulate.

In our case, we had the ideal role model right under our roof. We were extraordinarily blessed to have him as a father and for as long as we did.

His departure is going to leave a huge void but the lessons gleaned from his example will live on.