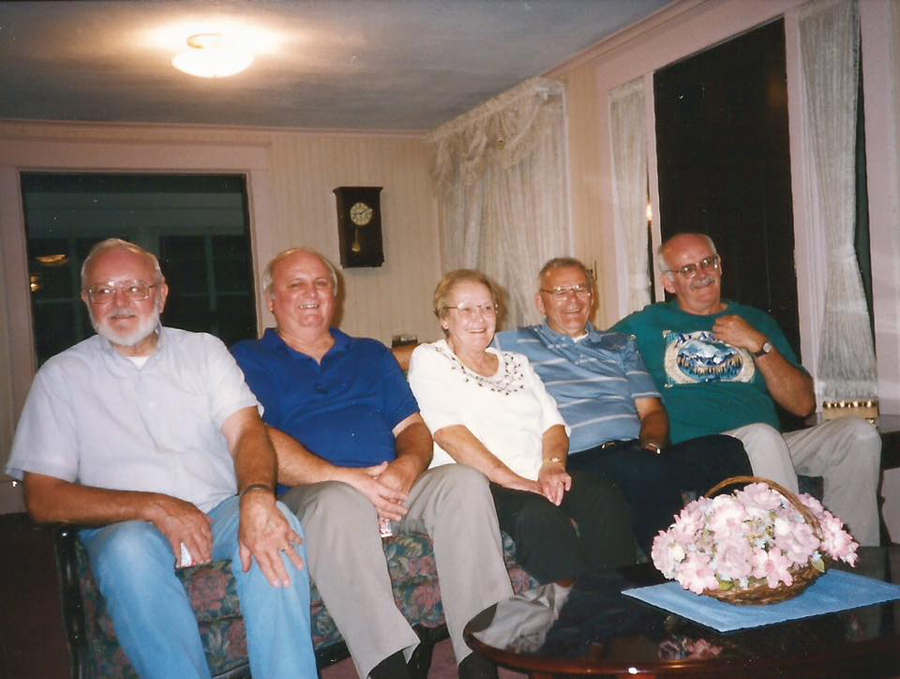

Above: Ray Mosher, David Mosher, Minerva Mosher Dean, Ron Mosher, Terry Mosher

My first recollection was as a newly minted five-year-old riding a school bus to my first day of kindergarten. It was a beautiful late summer day in September 1945, and I held the hand of my sister, Minerva, the oldest of us five children in the family, as we rode the mile to the old brick-building on North Main Street in our little New York Village nestled amid the foothills of the Alleghenies close to the Allegheny River.

As we got off the bus in front of the school, my sister tugged at me so we could walk the quarter mile to the old Masonic Temple where Kindergarten classes were held. I resisted. I suddenly panicked. I didn’t want to go to school. As my sister tugged in one direction, I tugged back in the other. A tug-of-war ensured and tears flowed.

There we were –antagonists, one an incoming senior nearly 11 years older than the little boy, waging a mini-war in the middle of North Main to a stalemate. Bribery has solved a lot of problems over the centuries and the incoming senior went to that.

“I’ll give you a penny if you come with me,” she said.

Wow, a whole penny! You could buy a red cinnamon candy disc with that. The deal was made, and I went to my first school day, unhappy to be there, but firmly clutching the penny in the pocket of my new pants.

It wasn’t a positive start to school. Miss Wormer, the teacher, gave me instructions on the rules of this new life. One was I was not to play the piano sitting along one wall, a stoic reminder that this wasn’t a normal kindergarten classroom.

A miscreant could also be the recipient of a dunce cap, which could be embarrassing to say the least. I was a free-thinking spirit of boundless energy and was a wild stallion that had yet to be broken. So, of course, I was the first to receive the dunce cap, on the first day of school no less.

Told to sit on the piano bench and warned once again not to touch the keys, I, of course, had to test the limits of that rule.

Maybe if I had been a better piano player, I might have gotten away with it. Miss Wormer was not pleased. I wore the dunce cap longer than anybody before me. It’s a dubious record, but at least it’s a record.

I learned early that I could throw the ball further than anybody else my age. Don’t ask me why. I just did. I also learned I could not run as fast as the girls, who as concession to the times were asked to wear dresses. As I progressed up the elementary school ladder, those girls seemed to get faster.

But there was one game where speed of foot was not necessary and in it, I was an equal to the two girls – Joan and Martha Jean. Yes, it was Jacks. We three would clear out the desks in the back of the room, knee down on the floor and spent all of our lunch hour beating each other.

I had good hand-eye coordination ‑ again, don’t ask me why I did, I just did – but Joan and Martha Jean were good, also. Our games were spirited and thinking back I think we all came out about equal in wins and losses.

For some reason, playing Jacks led me to experiment with putting pennies evenly spaced on my arm and in swift motion throwing my arm up to allow the pennies freedom to float in the air. And then it was my job to pick them off one by one before they hit the floor. I became very good at that. There was no use for that little trick as life moved on, but it did amuse me for short periods of time.

In the fourth grade, it was common for kids to have silver-plated toy pistols that could be used with caps to make it sound like the gun was fired with real bullets. For some reason, I had a couple rolls of caps, but no pistol and was just outside the door to the old school’s gym using a small rock to set off the caps one by one by hitting them with the rock.

Bruce Ritz came by and sat down and watched me and then decided to speed up the process. He grabbed a bigger rock and threatened to throw the rock on a roll I tried to shield from his devious motive. I figured Bruce would not throw the rock in my hand.

Wrong.

My hand still hurts when I think about it. It didn’t break any fingers but scraped some skin off and my hand bled a little. But it really hurt. I chased Bruce onto the playground, finally caught him, took him down and pummeled him. He was impervious to being hurt. He just laughed and finally I gave up trying to make him cry.

It was in fifth grade that I received my first notice from the other side. When I say other side, I mean spiritual. I’ll talk about this as I go on. But the first notice of something different about me was when I was just five and I used to have these visions of traveling into endless space. You might think this was both exciting and very scary for me. They came so often I began to think this was normal.

It’s difficult to put into words what this experience was like. But in general terms I got the feeling that our world is endless. There are no limits. Being bound by gravity to earth is elementary because those experiences showed me there is much more to our existence.

The main thing I got out of it was that we are not bound by space and travel. I was shown that travel through space can be done through anti-gravity ships that are powered by powerful energy. I was told that they would be available to us at some point.

There was also a suggestion that travel is only impeded by thought and if you believe you can be someplace you can be there in an instant by thinking about it.

So, we’ll see. All I know is that those experiences left me at some point, and I think they left when my mind started to adapt to the life I was given on earth (i.e. more concerned with playing Kick the Can than traveling into space).

I was a normal kid in between being connected to the other side. The polio scare in the late 1940s turned my concerned mother into a guard against doing things that might bring the disease to me. A brother of my father died as an infant to polio and my father was felled by it but survived with just a slight limp to him.

My mother warned me that I was not to swim in the Allegheny River, which served as wet boundary backyard to our home. The Allegheny was then, and is now, an old and slowly meandering body of water that in the middle of summers could be walked across and not get wet above the knee.

We neighbor kids played in the river almost every day in summers. We even had a thick rope somebody had tied to a tree on a little island on the river and we guys would swing out on it and drop into the river. You had to time your release from the rope just right to make the six-foot deep hole just a few yards away from the island, which was daring-do enough for me.

This is a roundabout way of saying Mama’s instruction not to swim in the river was not followed by me. It gets hot and very humid in New York in summers and one way to keep cool was to wade in the shallow river or to take the risk you could hit a deep hole and let loose of the rope as you swung out from the island. I did plenty of both, and if my mother knew she never mentioned a word.

I believe it was the Grossman’s that built a kayak and we extensively used it to oar up and down the river, crossing under the shaky Steam Valley Bridge that shook every time a car crossed it, which was infrequent (they have since built a different bridge a few hundred yards north, and is now closer to the island where we used to swing out on that rope), and visiting the breeding ground for the many carp that roamed around the bridge.

I had a Tom Sawyer childhood, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. The 1940s were a difficult time for our country – indeed the world – with millions being killed and maimed both physically and emotionally by World War II. But to a kid like me it was an idyllic life, full of Tom Sawyer adventure in a region where the Allegheny and the foothills of the Allegheny’s were a forest of paradise where kids like me could roam often barefoot and experience the peacefulness of the quiet forest and the sleepiness of the River in summers and skate on ice ponds and sled and toboggan on gentle sloops during the height of winters that were blanketed in snow from mid-October to April Showers when the first sign of green peeked out from the melting snow.

Hockey on a pond behind the Coswell Restaurant grabbed me in its cold vice for much of the winter. We used to fashion hockey sticks out of any available piece of wood and used empty cans as pucks and battled away with a mountain of fun. One year, we even built a fire in the middle of the pond for warmth, although I still don’t know how that worked.

The statute of limitations has run out on what us neighbor kids did one night to the outdoor market run by King Solomon (yes, King Solomon). King used to put a green tarp over the produce at night, figuring I guess that it would protect them.

Wrong.

One night the gang of four – me, Eddie, Gary, and Tommy – raided the produce. We left telling evidence, a smashed watermelon in the middle of the highway. Once was enough because we never did it again. I’m assuming King could figure out who the villains were, although he never said a word. Maybe he just charged more for the meats he sold that our dads purchased there.

Something that surprised me was later when I was going to college near there; I stopped in to say hi to him and noticed he was selling carp. Boy, if I had known he would have purchased carp, I and my fellow neighborhood guys could have sold him a ton. We used to catch them in the Alleghany and discard them by throwing them on the bank. We had been taught carp was uneatable.

A lot of time was spent by me on top of the dike once it was completed in the early 1950s. I would take a stick – a broomstick was ideal, but it was difficult to get them – and hit rocks. I would play a baseball game in my mind. A swing and miss counted as a strike and three swings was an out. It was also an out if the rock failed to make it to the river.

A rock hit into the river short of halfway was a single, a rock that made it half-way into the river was a double and it was a triple if the rock landed three-quarters into the river. Obviously, I had to do some quick calculations in my head because this was not an exact science, and because I played against a made-up opponent, the opponent didn’t get the same considerations on distances the rock sailed. Although, I made sure the cheating was close enough that no court would convict me of fraud.

If I could hit a rock over the river and into the trees on the other side – the Steam Valley side – it counted as a home run. It took some time before I could do that. But once I got the hang of it the rocks sailed not only into the trees, but a few sailed over them.

I would spend hours hitting rocks on the dike with just the sound of a rock hitting a stick breaking the silence. It was one of my best memories from my childhood. I discovered while doing this the slumps major league hitters talk about. They are real.

When I became older I came to understand these slumps as a by-product of being alive. Life is full of a series of ups and downs and this I found is persistence in everything we do, including in card games. But let me explain.

In my rock-hitting there would be days that I could close my eyes and hit the rock with my wood stick. And the rocks would sail uncommonly far. Then there were those frustrating days when no matter how hard I tried, I could not hit a rock. I would swing and miss, swing and miss, swing and miss. Finally, I would take a rock and hold it close to the stick and hit it. It wouldn’t go far, but at least I hit it.

So, I concluded that when Major League hitters go into a hitting funk and mess around with their swing and stance to get them back on track, they are wasting their time. It’s just a natural flow of life. They are experiencing a down period. For good hitters who understand it, they don’t change a thing and just wait it out, knowing that eventually the ball will look as big as a basketball and hits will flow like water from a tap. And that is what happened to me. Eventually, the rocks would fly into the trees on the other side of the river.

I played a lot of made-up games while playing cards in my idle time. I played a baseball game where aces were home runs, face cards and 10s were base hits and single digit cards were outs.

The same life ups-and-down occurred with single digit cards appearing more frequently in a down period and aces, face cards and 10s more often in up periods.

I also played football and basketball games with the cards, switching sports with the proper season ‑ football in the fall, basketball in the winter and baseball in the spring. In the summer, I hit rocks.

I’ll admit I used to cheat in the basketball and football games. My team always got a few extra cards for each quarter. Points were accessed based on the face value of the card with aces being one in football where the scoring was done with just aces, 6s, 7s, 10s and face cards. In basketball, face cards were given 11 points for a jack, 12 for a queen and 13 for a king.

I kept season records for all three sports on paper. Baseball was for a 154-game season, football for 10 games and basketball for 20 games. Again, life’s ups and downs would happen in all three sports.

Living in a small American town (population around 1,000) nestled in some of the most beautiful part of our country was wonderful. I was just a small boy during World War II but would keep up with what was happening through the only daily newspaper in that region, but mainly was unscarred by the war as so many other families were. The only real connection I had with the war was the popular call for scrap iron to help build the war machines needed to fight that terrible conflict. I used to go around with my wagon seeking whatever scrap iron I could find.

I started reading when I was five years old. I used to lie on the living room floor near my mother and dad in the evenings and read. My mother would knit, my dad would read the newspaper, and I would be sprawled on the floor reading the James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. – The Pathfinder and Last of the Mohicans.

Because I did not have an extensive vocabulary at that young age, I would skip the longer words and reading by paragraphs would figure out what the word meant and go on from there. Little did I know at the time that my habit of reading by paragraphs and skipping over words that later it finally dawned on me why it took so long to figure out how to correctly spell. It’s because I was skipping over them and digesting the paragraphs and the meanings without properly taking time to pronounce words.

At the time, though, it helped me get lost in the Leatherstocking Tales. I could almost see myself trampling through the Alleghanies, hearing the twigs snap under my feet and getting goose bumps on my arms with the scary fear of what might be stalking me.

Those were wonderful moments because I felt safe and secure being close to my parents in the peaceful quiet with just my thoughts getting lost in the woods as I read more of the Leatherstocking Tales.

Even then as a very young boy, I took to going into the surrounding hills to experience for myself what I was like to be alone in the woods. I used to get up on a ridge and sit quietly, taking in the beauty and having my breath being taken away by the small animals—squirrels and chipmunks – that would scamper about, unaware I was there, or not concerned that I was.

Once while I was up on the hill behind Linn’s farm, I was startled to see a black panther zoom past below me. He didn’t see me, but I saw him. I have always wondered if that is why our school’s mascot is Panthers, and there is a statue now outside the school of a black panther.

Years later when I was a middle-aged adult, I would go back to my hometown every so often and I made it a tradition to climb the hill behind my sister’s house, which was across the highway from where we both grew up.

The last time I did it I was half-way up the hill when I heard a frightening noise and some brush being moved. Terrified, I stopped and squatted down. I listened as the noise turned into what seemed to be heavy snorting. Too frightened to move, I waited it out and after what seemed like an eternity, the noise stopped.

When I told others what had happened, they surmised that it was a deer that was circling me. I don’t know, but it was scary. Maybe it was Bigfoot.

Life as a kid back there in my old stomping grounds included the occasional climb up the steep side of a gravel pit. We neighborhood buddies would do that climb at least two times a summer. I guess we would get bored and seek something different. And it was different.

It took me a few years to traverse the climb all the way to the top. That is because the top of the pit was a lip of turf that stuck out and you would have to bend back and arch your way over the top. It was a frightening one I refused to attempt for fear I would then fall backwards down the steep side. I wasn’t stupid.

But then as I got older, probably 11 or 12, I got to the top and dared to make the more that scared me. I pulled it off and found myself safely on top. Then another problem popped up. I could not go down the way I came up and I had no idea how to get back home from the top because I had never been up there before.

So maybe I was a little stupid.

I started walking through the woods on top and finally came to a road. It was the Promise Land Road, which is famous in that neck of the woods for a short part of the road that appears to go uphill, but if you park on that spot, the car will roll backwards, defying the law of gravity. I never heard a proper explanation for this. The closest was that there was a magnetic force there. But why would that make a car do something it shouldn’t?

The hill behind my sister’s house was a favorite playground for us. We could make the large climb to the top and then go down the other side into what is called Lillibridge, which is a winding road going past old farms that used to house dairy cows but were now mostly shut down and stand there now as a reminder of what used to be a thriving area.

On the bottom of the other side of that hill is a huge area of rocks, some bigger than houses. We used to climb all over them. It was great fun, although I don’t know why it was fun. It just was.

Those rocks – in the nearby big town of Olean there is an area called Rock City where the same size rocks, but more of them, can be found. My knowledge of that, which was passed down to me, was that those rock deposits were a product of a glacier that carved out the hills and valleys that dominate the landscape.

There was evidence that it might be true. I would find fossils of sea creatures in the hills (also crude arrow heads, presumably left there by Native Indians at some point in history).

Why nobody questioned why those rocks were there has always bugged me. I accept the theory of a glacier depositing them. But I can’t be sure. And nobody ever questioned why. In fact, if we kids had not one day climbed blindly over the hill just because it was there, we would never have known they were there.

That is an indication of the life that settled there. I don’t recall anybody questioning their existence. They were just there. So was I. But I often wondered what lay beyond our little village, the hills and river? What was the rest of the world like?

When I was 10, I rode my bike half-way to Buffalo 68 miles away. I was determined to discover the rest of the world. I got tired and turned around, but I’m glad I did it because I could see that there was a different world out there.

That bike was my proud possession because it got me places, and a lot faster. We had a wrap-around porch at our house and for some reason I thought it a good idea to bring the bike up on the porch, take it back to the end of it, and then ride it as fast as I could and fly off the porch into our side lawn. I figured out that to do it successfully you needed to lift the front end of the bike as you came off the porch. That provided for a safe, if a little bumpy landing on the lawn. If you didn’t do that you had a chance to going ass-over-teacups, you are going one way and the bike another. But I always made it safely, and it didn’t take long for that to be too boring to continue to do.

It gets hot and humid in the summers and we kids welcomed the rain, which followed black clouds rolling in, thunder and lightning and then a downpour unlike anything you can imagine. It was like somebody above poured buckets of water.

Mama used to chase me inside at the first sign of those black clouds because of the danger of the lightning bolts. But I could not wait for the rain to start because it was a way to get cooled off. We neighbor kids would rush out into the rain and get soaking wet in a flash, but, boy, did that feel good.

When I was very small and not too smart yet, I used to fashion a stick with some string and a hook and after a typical downpour “fish” in the small gutters on the side of the highway that ran past our house. I guess I had hopes of catching a fish. It took a year or two before it dawned on me that it wasn’t going to happen.

However, every few years the Allegheny would overflow its banks during spring run-off and there was a chance to catch real fish in the lawn and the road. The flood of 1948 I sat on the porch and watched as the water swirled around our yard and crossed the highway. And carp, which were plentiful in the Allegheny, would be trying to navigate the highway. Successfully, I might add, although it took some effort because the water was not really deep.

During one flood, and it might have been the 1948 one, dad had to get a boat and oar to our house and rescue his family. He had been at work in nearby Olean and could only get within a half mile of the house. He got a boat and made it the rest of the way.

Before the dike was built to hold back the swollen spring Allegheny, my father used to measure how the river was rising by placing a stick in the ground and then coming back later to see whether the river was rising or falling off by where the water was in relation to the stick. I remember our basement flooding as the river rose. I know one time the water was three-quarter the way up the cellar stairs.

You know, I never felt scared of flooding. For me, it was a good time to do some fishing off our porch.

Summers were brutal. The oppressive heat and high humidity made it almost impossible to sleep. My bed was right next to a window that looked out over the roof of the porch. I had a screen on the window to keep critters out, but it provided little relief from the heat.

I finally learned that the best way to beat the nighttime heat was to go out on our side lawn and sleep there. Sometimes I would go out on the porch roof, but that wasn’t as comfortable as the lawn.

My three older brothers – Ray, Ronnie, David ‑ had an escape route from our mother’s demand that we go to bed. They taught me how to go out on the porch roof and jump from the edge of it to an open window to the upper floor of the garage.

That leap of faith took me some time to brave it because if you missed, you fell to the cement patio below. I can still see me going up to the edge and then backing off. It took a lot of courage to make that leap. And it took me a long time to do it. My brothers, being bigger, did it easily. When I finally achieved it, I felt a great sense of independence. Now I could roam at night knowing my mother felt I was safe in bed.

In the 1940s and 50s I was living in a small village nestled in a place that I got used to calling Paradise for not only its beauty, but its quietness and isolation from the bigger outside world. My world – my Paradise – was perfect in every way, fall, winter, spring and summer (discarding the heat).

We lived a mile from the center of town, which consisted of a red light, half-dozen stores (hardware and barber shop being the foundations) and a place called the Colonial.

The Colonial. It was THE place for us. It consisted of a town hall, which I had never seen. It was downstairs and I never went there (rumor has it that town officials played poker down there at night, but I wouldn’t know about that). On the main floor – the only floor – on the right was the post office, in the middle was the movie theater (school plays, out-of-town entertainers and graduation from the school were also held there) and on the left was the soda jerk place where all the young people in the village met. It was the nerve center for us. You wanted to find somebody or meet somebody, you went there.

From the lobby of the Colonial, you turned left and opened a screen door to the soda jerk. As you entered, right in front of you was a glass enclosed case holding candy for sale. I could purchase a red cinnamon disc for a penny, which I often did.

Turning left you enter the main floor of the soda Jerk. There were high-back booths along the wall that included a juke-box selection box (a dime got you two music selections) and room for six people if you squeezed really tight together. There were six of these booths.

On the right were bar stools and a counter where you ordered cokes (Green Rivers, root beer floats and banana sundaes were the big hits). There was also a magazine rack and a comic book spindle against the wall where you entered.

The juke box was at the far end against the wall next to the back door that emptied onto Temple Street.

I loved to walk or ride my beat-up bike the mile from our house to the Colonial in the spring, summer and fall and sit on the Colonial steps. There were four great concrete columns that rose from the steps – two on each side – that held up the façade and I used to play around them. I’m not sure when the Colonial was built, but I have seen a picture of it from 1906 when it was considered the town hall.

On summer weekends when traffic on the road – Route 17 – was especially slow, Pa Fischer, the village’s lone policeman would come to the Colonial and sat, waiting for somebody to run the lone light or to speed faster than the posted limit of 25.

Pa owned Fischer’s Restaurant in the village where my sister, Minerva, worked for years as a waitress. He was a slightly over-weight man whose pace of walk was slow and slower. But he was a gentle soul that watched over us rambunctious village boys and when a traffic violator was seen by him would often invite one of us to go along with his traffic stop. It was a special privilege to do so.

Neighbors back then were kids’ finders. If my mother wanted to find out where I was, she would make calls to neighbors and they would inform her they had seen me just a few minutes ago walking through their corn field, or some such thing.

Pa was part of that family network. Sometimes we neighborhood guys would get into a corn field and smoke the corn husks, or at least try to. Invariably, the next day Pa would sidle up to us and say, “So you boys were smoking husks yesterday in so-and-so’s corn field. Maybe you shouldn’t do that.”

One time he informed us that somebody stole some corn from Dean’s corn field and asked us if we saw anybody that might have done it. He knew, of course, who did it.

The warning was well-taken, but normally didn’t deter us from committing the same infraction in another day. And we’d get the same caution from Pa. “I know where you were yesterday,” he would say. “I’m, watching you.”

But Pa was a good guy. He was like our second father, and we knew he would not allow anybody to harm us. He was our protector, even if he had to chasten us every so often.

If you need to know, drivers that got caught by Pa were taken to the village’s justice of the peace where they were required to pay a small fine. It was a traffic trap that almost all the small towns – and there were towns every few miles ‑ in that section of the state used. It was a way to raise a little poker money for guys like Pa and the justice of the peace. A nice con, if you will.

My mother – Jessie Eilern – did not like my dad stopping for a beer on his way home, but he still found a way. Numerous times I was in the car when he said he had to stop somewhere to see a man about a cow, or sometimes it was a horse. Funny how all these stops were at local beer gardens. I would be left in the car while he went to see about these animals. I think most of them – maybe all of them – were named Genesee (as in beer). One day my dad had an unfortunate stop at the Highway Inn, just a half block from our house. Unfortunately, because my mom found out he was there and walked down there, went inside and grabbed a chair and began hitting my dad over the head and shouting for him to get home.

He did.

My mother was five-feet-two and one quarter of an inch tall. My dad was six-foot-three and the most powerful man I ever knew. He was a farm boy, and they grew those boys strong back in the day. But my dad was also the most peaceful and loving man – a gentle giant.

I never heard my dad swear or say a bad word about anybody. The closest he got to swearing was the one time he was at the bottom of our basement stairs, and he asked me, standing at the top of the stairs, to throw him one of the bricks that lay at my feet. I did, and it hit him on top of his head.

“Damn,” he cried out, “why did you do that?”

You told me, too, I replied.

Dad raised just about everything in a garden. We had chickens and turkeys. The turkeys were the most frightening for a young kid. They surrounded me and I could not see over the top of them. I felt like they were going to eat me. To make matters worse, my mother would tie me to the clothes lines where she hung things to dry and I had no place to run when the turkeys came around. She tied me there because she was trying to make me safe, but it didn’t feel safe to me.

We had an empty chicken coop when the 1948 flood arrived with the Allegheny overflowing (our house stood along the river), but as water washed into the coop, we quickly discovered it was not empty.

Looking out from our sun porch one morning, we discovered rats were everywhere – on top of the chicken wire fence posts, on our lawn and looking longingly at our house. It seemed like there were hundreds of them. Wow.

My older brothers ran into the house and emerged with a short-barreled .22 rifle.

They began shooting at the rats like they were empty tin cans. My brothers were very athletic, but terrible shooters and not one rat suffered. Nor did they move. They were caught between the devil and the deep blue sea and were easy targets. Fortunately for them, my brothers couldn’t shoot straight.

When my brothers started playing high school sports, I was a frequent watcher. Football games were played on Saturday afternoons behind the old Portville Central School on N. Main Street. A rope line separated fans from players. There were no bleachers, and the smell of hot dogs filled the air.

My dad and I roamed behind the rope line moving as the action on the field moved. It must have been 1950, the second and final year of my oldest brother Ray’s postgraduate (PG) status that I rode with dad in our new 1950 Plymouth to a playoff game in a town I can’t remember now. I do remember it was very cold and there was maybe six inches of snow.

My dad and I sat in the car to watch the game. He drove the car right up to the field. And I remember at some point in the game my brother Ray’s pants split right down the middle in the back. My brother denies that now, but I know it happened. I saw it. I believe Portville lost 6-0.

Ray played football and baseball. He could have played basketball but wanted to take some time off from sports. He would have been a good basketball player. He was the quarterback on the football team and an outfielder in baseball. He was a tremendous hitter. I saw him hit a ball over the First Presbyterian Church Steeple into N. Main Street. He denies that, too, but I saw it.

Dad didn’t finish his sophomore year of high school and went to work for Socony- Vacuum at its refinery in Olean, NY as a young teen. He would work for the company, which became Mobil Oil, for 37 years and never missed a day’s work. And he often would take somebody else’s shift to work 16 hours.

The reason I bring this all up is that Dad didn’t quit high school. The high school (Hinsdale, NY) quit him. The story he told is that he was playing baseball for the school team and hit a home run, and the ball went through a window on the third floor of the school, breaking the glass. The school wanted my dad’s parents to pay for the glass and they refused. In response, the school kicked dad out of school.

If you think blasting a home run to the third floor of a school is unreasonable, you don’t know my dad. He was 6-3 and 225 pounds of sheer muscle. It wasn’t muscle build on lifting weights at a gym. In fact, they didn’t have such things when he was growing up. Weightlifting was discouraged even into the 1950s by schools.

No, dad’s strength was natural, and it came from growing up on a farm on the Five Mile in Allegany, NY. Dad was the most powerful man I ever saw. But he was very gentle. A gentle giant, if you will.

One day at work – dad oversaw the boiler room at Mobil Refinery on Cherry Pt near Ferndale, WA – a co-worker rushed in and in a panic said they needed my dad’s help. A big pipeline valve had gotten stuck and six guys using a long wrench failed to get it unstuck, so they sent a guy to look for Big Mo, my dad.

Once dad figured out what was going in, he went out to the pipeline and grabbed this long wrench, locked it on to the valve and with a mighty pull opened the valve. He put down the wrench and walked back to the boiler room. His six co-workers, their jaws wide open in disbelief, just shook their heads and went back to work.

Dad didn’t know his own strength. He just figured everybody was like him. Wrong. There was the time Dad purchased a new motor for our 1950 Dodge, and he had assembled a system of chains and pulleys in our garage he was going to use to pull the old motor out of the car. He wrapped a chain around the motor and asked me to keep it straight so it wouldn’t hit the frame as he pulled it out.

I couldn’t do it. I just did not have enough muscle to wrestle the motor. Dad got frustrated with me and said, “Come here, you pull it out and I’ll keep it straight.” I took a couple steps toward him when I realized the absurdity of it. I did not have the strength to do that. I just said, ‘Okay, I’ll keep the motor straight while you pull.” And I did. I don’t know how, but I did.

Then there was the time I was helping him build this house and we had gotten to the point the roof needed to be tarpapered. He had purchased a large pile of rolls of tarpaper and grabbed two of them, putting one on each side of his shoulder and started to climb up a ladder to the roof. As he climbed, he said to me,” Grab a roll and c’mon up.”

I should have known better. I grabbed a roll, put it on my shoulder and walked to the ladder. I managed to put my right foot on the first rung of the ladder and that was the best I could do. By now, I was used to being the lightweight and just shrugged it off. Dad had to lug those rolls up the ladder.

This is a story my brother-in-law, Alvin Dean, told. He was told by my dad to hold a wrench to a pipe while my dad on the other side of the wall would loosen the pipe. As dad cranked on the pipe on his side, Alvin on the other side was flipped upside down by the force my father applied. Alvin never tired of telling this story.

Farmers in the old days were people who farmed to provide their families with life. Our country was mostly agriculture, and the lifestyle birthed strong bodies. My grandparents and my father and his brother Bob were prime examples of people with natural strength built on their family farm on the Five Mile in Allegany NY.

As the youngest in a family of four sons and a daughter I recall working on my grandparents’ farm at a very young age. I would be running behind a tractor pulled flatbed wagon trying to lift bales of hay onto the bed as my older bothers kept yelling “hurry up.” I was six years old.

Once I stood outside my grandfather’s milk house, which was really a shack without a floor built over a running creek. Those stainless-steel milk cans were placed in the creek to keep cool until the milk truck showed up to take them away for processing. As I stood there my grandfather, who was a man of few words, said to me “pick up the can and put it in the milk house.”

Again, I was six years old and probably as weak as you would imagine a six-year-old to be. But if you were on his farm, granddad expected you to work. So, I obeyed and muscled that can until I had it in the milk house.

Lunch at my grandparents’ house was a special treat. They also raised chickens so sometimes my plate would include a complete chicken and other times there would be a big slab of beef along with potatoes. And milk. Always there would be milk.

That’s where I learned an early lesson. On family farms you and the farmhands were expected to eat a formal lunch with piles of meat or chicken to give you fuel for the hard work you did and were expected to do. Of course, each lunch was topped off with a pie of some type, usually apple because the farm had apple trees. The pies were topped with ice cream.

That brings me to my grandmother. She was always cooking in the kitchen. I can still picture here there, along with my Uncle Bob’s three daughters and my sister Minerva, all of them cooking up a storm.

In the late 1940s work began on the dike system that was being built to hold back the Allegheny and avoid the floods that came every few years. Before they were finished, we kids used the piles of dirt to jump behind as we shot at each other with our bee-bee rifles. The only rule is you could not shoot in the face.

Once the dikes were finished, they served as a walking path for me. Walking up the side of the dike was as easy as climbing the darken steps to my bedroom. I took one easy step at a time until I reached the top and then I looked down at the little white house next to our house and gave out a shout, “Hey, Dean c’mon out.”

Seconds later he appeared; thin as a rail but standing as upright as usual, as if he was saluting our flag. Dean scrambled up the dike and once assembled we moved slowly down the dike, bending down every few steps to pick up a small rock and throw it as far as we could into or over the slow-flowing Allegheny of our hot New York summers.

It was post-World War II still and soon the valley would echo with the soothing sounds of the local legion drum and bugle corps practicing their patriotic music before members would head off to their respective legion halls to wet their throats with cold brews that were local to the region – Iroquois and Genesee (Genny) – and tell their war stories if their throats got wet enough to loosen the horrors they survived.

Dean and I stubbed our feet, kicking up small rocks, and the humid air drew beads of sweat on our brows as we mindlessly neared the Steam Valley Bridge, an unstable structure that rocked back and forth when the occasional car rolled across its bumpy asphalt pavement.

We talked sparingly. We were just two young boys devoid of responsibilities wandering in the heat while allowing the beauty of our surroundings paint a picture that would sustain us for years, long after we were young, long after we lost touch with each other, long after we created our own nests and moved closer to our destiny, where ever that was to be.

We scrambled down the side of the bridge, letting gravity take us to the edge of the meandering Allegheny and the stink of rotting carp that others had thrown on the brushy bank.

Nestled safely under the bridge and listening to the rumble of the lonely cars that would shake the bridge, we were suddenly quiet as we surveyed our small surroundings and we moved our heads quickly to the side whenever a fish, usually a sucker, would rise to the surface for a breath of the humid air.

It would be only days now that I would leave the comfort of this hiding place underneath the bridge. The hours were ticking away when I would throw my last stone into the Allegheny, see my last sucker, smell my last carp, kick my last rock on a dike that was my playfield where I hit stones with a stick for hours into and over the muddy river.

When next I saw Dean he would be just over six feet and he would be between the Air Force and several long hitchhiking rides to Virginia where he would build his nest and I would lose contract with him.

We didn’t say much as we climbed back out to the dike and slowly walked back to our next-to-each-other homes. What could we say? He was staying until at least four more years until his service in the Air Force and I was about to be uplifted to a long cross-country journey to the mystery of the Left Coast and a new life far from the lazy Allegheny and from Dean.

One last time we each tossed a rock into the Allegheny. One last time we looked at each other. Then without saying goodbye to each other, he slowly turned and gingerly made his way down the dike. I watched as he crossed his lawn and disappeared for the final time into that white house.

I took one last look at the Allegheny, bid a silent farewell to my old friend, and turned to make the same descent down the side of the dike and make my way across my lawn and into the house where I was raised that was now absent my mother who laid buried 15 miles away in a peaceful corner of a cemetery that silently endures the changing seasons year after year after year after year like so many loud ticks of a second-hand on a clock that has no ending.

My idyllic childhood ended that day and the long nightmare that would comprise my dark years would begin.

I would meet Dean years later when he was out of the Air Force, and I was headed to college in New York State.

That accidental meeting was only brief. We would enjoy a beer together not far from that bridge and he would depart that brief snapshot and head to his destination. We were now different people with different thoughts. The years of separation had made that so.

Dean didn’t make it as far as I have. I discovered in April of 2020 that he was gone. His younger brother, William, had died and it listed Dean as preceding him in death. I could not find an obit on the Internet for Dean, so I don’t know when he died.

I hope Dean remembered that walk we had before he died, because that time, as short as it was bridged the gap between what was and what is. It was like closing a book and opening another. I didn’t want the new book, but I had no choice. That’s life sometimes. Sometimes you voluntarily make your way and sometimes you are dragged.

I was dragged.

But I did survive the drag, and I came out of my dark years. And, of course, I would wind up here.

Good or bad, this is it.

My dad and brother tricked me into going to Ferndale, WA in late August of 1954 as a caravan of employees from the now closed Socony Vacuum Refinery in Olean to the new Mobil Refinery in Ferndale nestled along Cherry Point, which was part of Puget Sound, trekked west to a new life. Many of those who made the trek are now dead, including most of my buddies. They were the light that shined on my dark years. They might have saved me from an early death.

Our first home was a farmhouse rental where I survived only by taking long walks across an open field and into some dense woods before emerging into an open plain that ran along the Nooksack River.

I was not wanted by my dad’s new wife. She preferred her own two kids, three years and six years younger than me. Linda, the oldest, died Nov. 30, 2024. Leon, the youngest, lives half the year in Arizona and summers and early fall in Washington state. Whatever trouble erupted, I was immediately the blame, even when I often was not.

My dad didn’t know what was going on and I never told him. I didn’t want to hurt my dad’s marriage, so I suffered in silence. Hiis wife abused me emotionally. So, I stayed away from the house as much as possible, taking long walks along the railroad tracks and woods.

I subconsciously tried to commit suicide several times during my dark years. There were numerous times I got my dad’s DeSota going 140 mph without any concern that maybe a tire would blow out or I would overcorrect and cause the car to spin out of control.

I also drove the car up to 100 mph on dirt roads, causing a buddy to turn white and cuss me out as I flew the car through the air while hitting humps in the road.

There was cliff diving and the especially bad day when I wandered along the banks of a surging Nooksack River and contemplated whether I could swim across it. I sat on the banks for a long time thinking about it and finally decided against it. I probably would not have made it, although I was willing to die trying. Almost.

When I was in the house, I stayed in my upstairs bedroom so trouble couldn’t follow me. I had an upright radio for years and it kept me sane. It played all night long and I would pick up WWVA from Wheeling West Virginia and the Grand Ole Opera and Louisiana Hayride. There was also a radio station that had a guy reciting poetry while waves crashed in the background.

I could pick up KGO out of San Francisco that at night had Ira Blue broadcasting jazz and interviews with legendary musicians and famous baseball players. I loved this show and the combination of it all soothed my tangled nerves from the abuse I was taking.

As a young adult many years later, I was driving late at night, coming back from covering for the Bremerton Sun newspaper a Seattle Mariners’ game at the Kingdome, and it suddenly occurred to me that my father’s wife was not at fault. A voice telepathy suddenly told me as I drove down 11th street in Bremerton, WA. “She is dumb.”

Bingo!!! She was just dumb. Stupid, really, and had no clue how to be a mother, not to me or to her own children. As I drove on into the darkness that night, I forgave her for she didn’t know what she was doing. It didn’t make the agony of my dark years any better, but I could now have an answer why it happened.

Because I stayed away from the house so much, to avoid the hurt, I did not eat often with the family. As a result, I was stunned by my growth. I grew to six-foot-five, but I believe I could have grown much taller.

Those dark years started with me being bullied on the school bus and I answered that by walking to school, three miles each way to school for the next three years. What is amusing, at least now, is as a college student I became friends with one of the bullies. I never brought up the subject of bullying with him and I don’t know if he even remembered. But I did. And I still do.

This would not have happened at my old school in Portville, NY because I was considered the latest member of a solid gold community family that included three very good athletes and very good students. I was the best athlete in my class and one of the best in the school, and I was a B+ student who excelled in math.

I was ticketed, at least in my mind, for a very good high school career in sports – football as quarterback/linebacker, basketball as a guard with height and baseball as a great hitter with a strong arm (I figured to be a shortstop or a corner outfielder, but not a pitcher; I did not like to pitch and it probably was because in my neighborhood when we played baseball my buddies would not let me pitch because I was too good.

There were two instances in PE classes when teacher (coach) Charlie Miller called me out to show how to shoot a basketball and hit a softball. The basketball example was for me to shoot from 10 feet away from the basket. I made 10 shots in a row before Miller halted it. In softball, he had me hit it just once and I blasted the ball maybe 225 feet.

Anyway, I was a very good athlete. We used to play basketball in the winters in Linn’s barn and I was usually the youngest player. I had to figure out how to pass and shoot over guys much bigger and more experienced than me and I developed a no-look pass on the dribble and behind the back passes and learned to lean my body into a defender so I could shoot over him.

In all three sports, football, basketball and baseball, I played against my older three brothers and their friends and that helped me become very good, and much better than kids my own age.

But all of that went for naught once we moved across the country to the West Coast and Ferndale, WA. I was 14 and a freshman when we moved and my growth both as a person, an athlete and a student stopped right there. I did not participate in sports, did not participate in classes and if it wasn’t for a few guys that also transferred to the West Coast to Ferndale (from Olean, NY) who knows what would have happened to me.

I grew very close to Adolph Jonak, who had his own family issues, and he and I used to sit in his old Ford coupe and talk for hours in the dark hours of night with the car radio turned to KGO and Ira Blue from the Hungry I in San Francisco.

Man, those were good times. I got turned on to jazz through Blue, and Adolph and I became as close as friends could get. Until Adolph died of a fatal heart attack on Dec. 14, 2011, we would continue to talk by phone, he from his home in Los Angeles and me in Bremerton, WA. We had more laughs, and I miss him dearly. He married a sweet girl from the Smokey Mountains of Tennessee and he and

Joanne had the best marriage I have ever seen or heard about. They were close pals and close lovers and made sure they took good care of each other. Man, they don’t

them like that often.

My senior year I did tryout for the basketball team. It desperately needed help, and I tried and almost made the cut. I know the exact moment when I was cut. I had stolen the ball and was driving down the court when I ran out of gas and threw a wild shot from half-court. Up above me in the stands in our cracker box gym I turned and saw our coach scratch out my name.

My problem was two-fold. Little did I know until years later when I suffered a minor stroke it was discovered I had scar tissue on my heart from a previous attack. I also knew that I was vastly underweight from not eating or not eating right. and that caused me to miss hundreds of meals. But I was good with that. My body wasn’t, though.

There was one bright light during my dark years. In 1955 my father drove us back to Portville for a vacation. I had accumulated a big wad of money from working in hay fields and apple groves and I took most of that with me.

Two of my Portville friends found out I had this money, and they arranged for us to have a triple date. They both had girlfriends and needed to find one for me to make this work for them. They practically dragged me to the top of the Portville Fire Department Building, which I didn’t know existed. We walked up these long stairs and upstairs was a lounge area with a pool table and a kitchen.

As the three of us got upstairs, Fred pointed to a girl playing pool. “That is her,” he said.

Well, “her” didn’t satisfy me and I started back down the stairs. I wasn’t too happy being around girls in the first place. My life centered on sports and being alone to escape the darkness that had swept in on me once my mother died.

I got half-way down the stairs and heard Fred yell, “Mo, get back up here.” I turned and as I did a girl suddenly appeared between Fred and Bill at the top of the stairs.

What happened next happened in a period of seconds, but it seemed like an eternity. As I saw the girl, I could feel an incredible wave coming over me of peace and love. It started at the top of my head and continued down until it hit my feet. And in an instant, I pointed at the girl and said almost involuntarily, “I want to go out with her.”

I remember Fred saying I couldn’t go out with her because she was too young. And I don’t remember what happened from that point forward. What I do know is next summer I will go back to Portville again with dad driving us there.

As we got closer and closer to Portville I could visualize this girl, which I will call Sharon, sitting in a booth at the Colonial. In this vision she was sitting with two of her girlfriends.

When we finally arrived at my sister’s house, a mile from the Colonial, I got out of the car and without saying hello to my sister started walking to the Colonial. As I entered the Colonial, one of Sharon’s girlfriends saw me and moved over to make room for me. I walked over to the booth and sat down. I immediately reached out my hand and Sharon, sitting across from me, reached out her hand and we brought our hands together in a firm grip. The sensation running through me was immediate and all the darkness was gone, replaced by a bright light.

For the next 10 days we were together nearly every day, holding hands and talking and talking and talking. It was incredible. The feeling of love and peace and calmness was overwhelming, and our contacts were very innocent. We kissed, but also very innocently.

I remember one night we sat on the swinging couch at her parent’s house and after about an hour of absolute bliss, Sharon’s mother opened the door and said, “Sharon, it’s time to come in.”

Sharon and I spent two brief summers together, holding hands and talking. Those were the bright lights in otherwise darkness for me. Then in my senior year, on a spring day, I went to get the mail and there was a letter from Sharon. I knew what it was. I had given her my class ring and she wore it around her neck with a chain necklace and I could feel it right through the envelope.

I put the unopened letter in the bottom of my bedroom dresser, under clothes I never wore. I then took a long walk into the woods, emerging next to the Nooksack River, which was raging with the runoff of snow from the mountains.

For hours I sat along the bank of the Nooksack. My bright light was dimming, and I consciously considered a swim in the Nooksack to see if I could make it across its roaring waters. It was clearly an attempt at suicide. In the end, I decided against it after deep debate with myself. But I knew darkness was again going to be my constant companion.

It took me three weeks to open the letter and discover my ring and the necklace she used to wear it with. I read the letter, which I considered a “Dear John,” and then tore it to pieces and with the necklace threw it in the garbage.

Then I took a long walk along the railroad tracks, crying the length of it. I flushed out my grief and returned to my dark years, alone once again. I have no idea what was in the letter other than she had found a guy that would turn out to be her husband.

So it went for me.

When I graduated high school – I had to take a history course at Olean High School the summer of 1958 to get my graduation degree – I had went back east and went to college a Alfred Tech. I would most weekends stay at my sister Minerva’s house in Portville, otherwise I would have been living in dorms or at a fraternity.

The summer of 1959 my brother –in-law got me a job at his place of work – K-Bar Cutlery – and I got involved playing the Numbers, but never won. We also cashed our paychecks across the street from K-Bar at the Silver Slipper beer garden. The owner sat at a card table with a cash box and doled out your check in cash. He would keep the change for his effort. So, if I got paid $189.47 he kept the 47 cents.

Of course, we workers all had several drinks while there, so the owner made out pretty good. My favorite drink was always Iroquois beer.

I was scheduled to be a CPA and was taking a lot of accounting classes at Alfred Tech (now Alfred State), including business math. I was extremely good at math and when the class was finished the professor called me to the front of the class and told my fellow students that in all his years of teaching this class nobody had ever gotten a perfect grade until now. Then he pointed to me and said, “Terry has gotten a perfect grade.”

I wasn’t surprised, but all these years later it’s something I can point to as having accomplished. So, I got something going for me.

Late in the fall quarter of 1959 I was living with two other students in an apartment on the top floor of a house in Angelica, NY. We had to take long steps on the outside of the house to reach our apartment.

One night I was on my bed with a large profit and loss statement that I had to balance. I kept coming up a penny short. And I couldn’t find my mistake. Hours went by and in the next bedroom a roommate from New York City was playing Muddy Waters blues on his 8 reel-tape deck. He played the blues over and over and while the blues were pounding inside of my head, my head was pounding from the blues of not finding that stupid penny.

It was one o’clock in the morning, then two in the morning and then three. I had an Iroquois in one hand and a pencil in the other and as the clock ticked toward four in the morning I in frustration swept the profit and loss off my bed and told myself that was it. I was done.

I quit school and a month later four of us were headed to Los Angeles. It wasn’t a planned trip. It just happened. We were sitting around a table on a cold December 1959 day at the Old Rose Inn, a beer garden in Portville, playing Euchre. Dick Scott and I were partners and Amos Blakeslee and Dave Ryder were partners.

About an hour into Euchre, we were all half in the bag. Dick was drinking Genesee Beer and I, of course, was sipping on my Iroquois. Amos and Dave were drinking gin and tonics. We were four young guys – I was the youngest at 19, Dick was 20, and Amos and Dave were 22 – that had outgrown our little village of about 1200 people with its three residential side streets and its one red light. There was nothing going on for us. I had quit college and was treading serious water and my three amigos were stuck in neutral.

So, we were casually discussing what we could do when suddenly Dick, who had already been overseas and in the Middle East with his parents, said, “I know, we can go to California.”

Just as suddenly, Amos jumped up from his chair, a big grin on his face and his tonic slopping over his hand and dripping down on the dirty hardwood floor. He said in a loud voice, “Let’s go.”

Dave was the moderating voice. He cautioned against making a rash decision and said we had to plan it out. Dick said he had to switch his 1954 Mercury from automatic to stick before he could leave.

But a plan was hatched.

I helped Dick change out his transmission in the next couple weeks. Well, I handled him a wrench and held his beer as he did all the work, laying on snow-crested grown outside the Rocket Gas Station just across from the Toll Gate Bridge in Portville heading out toward Pennsylvania. Every so often I would go inside the gas station and purchase a poor boy sandwich from the machine. Then wander back outside in the cold to serve as Dick’s go-fer.

The plan was for each of us to put $35 in the glove department in Dick’s Mercury and with a case of soup and a case of beans, both donated to us, on a bitterly cold day started out for Los Angeles. The cold and the desolate area we lived in, and the bleak future for jobs, led us four to take a deep breath and leave our hometown and head for sun and fun.

And girls. We can’t forget the girls.

The first week or so in La-La Land was a little scary because none of us had money. We took turns calling home to have some green sent to us by the Western Union. We bedded down in a seedy hotel on Wilshire Blvd., debated such things as whether to buy food or liquor with our dwindling funds. Liquor always won.

We eventually paired off with Dick and I going to the beach and Dave and Amos flirting with LA. All three of my amigos are dead – Dick going first in 1962, Amos about 30 or so years ago and Dave a few years after that.

When I think back to those times, and I do quite frequently because they were good times, I get sad that I have no one to share those good -time memories with. We were all young then and full of it. We didn’t want to conquer the world, but we certainly wanted to enjoy the good parts of it.

One of the good parts was discovering Bobby Blue Bland, who died at 83 in June of 2013. Bobby Blue Bland was one of the first blues singers I came across – Muddy Waters was the first – and he came to me just days after us four amigos got to LA.

The first time I heard him was the night – about 2 in the morning – when we four drove right down in the core of downtown LA. There was hardly a car or soul around as the four of us passed around the remains of a fifth of whiskey. I don’t remember what brand. It doesn’t matter.

As we drove around the nearly deserted streets of downtown LA, the music coming out of the radio in Dick’s 1954 Mercury was Bobby Blue Bland. I have never heard blues so cool. Bobby Blue Bland still rings in my ears. He was coming to us from a black radio station and the DJ kept playing Bobby Blue Bland repeatedly.

And the weird part is that Dolphins of Hollywood sponsored the show. I had visions of Dolphins of Hollywood being a Victoria Secret kind of store, but it was as far from that as possible.

What I didn’t know then was Dolphins of Hollywood – and the name was repeated after every Bobby Blue Bland song ‑ was that the broadcast was coming from Dolphins, which was a 24-hour record store. The station – KRKD – was in the store with DJ’s spinning the platters all day and night.

There is a fascinating story on Dolphins of Hollywood at http://dolphinsofhollywood.com/home/about/history/. There you will find that John Dolphin became a legendary black businessman back in those times. According to the story, Dolphin wanted to put his store in Hollywood. The problem: he was the wrong color. Hollywood wouldn’t let black’s own businesses in its city.

John Dolphin did the next best thing: he took his store to Watts, and we all have heard of Watts because of the Watts Riots that happened five years after I left LA in 1960. Dolphin got even with Hollywood by naming his store Dolphins of Hollywood.

I instantly fell in love with Bobby Blue Bland and his music. And I fell in love with Dolphins of Hollywood, even though I never came close to stepping in the store.

I think the reason I fell in love with Dolphins of Hollywood is because of the way the DJs would pronounce the name. There was something mysterious and wonderful about it at the same time.

Of course, there is something about being a small-town boy of 19, being drunk in Los Angeles late in the night and feeling completely free for the first time in my life. I was far from relatives, far from home, far from everyplace, and broke like an empty and very broken piggybank. Yet, I felt good for the first time in years. My dark years were still with me, but I could see a little light.

It was warm out that night as we drove through downtown LA, the radio blaring Bobby Blue Bland, four guys laughing and all thinking how cold the friends we left behind were back in our hometown in New York State.

Life could not get better than that. And don’t spoil it by using modern terms to describe what we did that night. The world has changed and if my amigos were alive today, they would have settled in and would not be doing what four rambunctious guys did that night. But this was 1960 and four young kids had broken loose from our homes and had gone out on our own never to be shackled again by the comfort of our slow-paced hometown that we left behind.

I’m terribly sad, still, that Dick died so young, in a car crash that I somehow knew would happen to him. He stood for everything we were at that moment driving through LA. Dick had been around the world with his dad, working in the Middle East, and he had gone to school for short period of times in Montana and Vermont, and was about as carefree and as good a person as one can get.

I miss him, still.

What is even weirder, as I write this Bobby Blue Bland is playing on American Routes. A few minutes ago, I randomly went to the show’s archives for June 2005, and lo and behold, I stumbled on a two-hour show with Bobby Blue Bland.

He was our unofficial fifth amigo, and now we are down to one – me.

Dick and I settled in Hermosa Beach in a studio apartment a block and half from the beach on Pier Avenue. We became beach bums – body surfing and girl watching – during the day and at night we worked in Torrance, Calif where one night I ruined 2000 dollars of inventory in the Magnavox machine shop. Dick would mix whiskey with orange and grapefruit juice in a plastic quart container, and we would be off to the beach. On weekends, we often wound up at the Vogue Tavern located on the Hermosa Strand and sipped beer, I as an underage drinker.

This was an unbelievable time after World War II and the Korean Conflict and times were peaceful and prices were good. You could purchase three hamburgers for a dollar, beer for a quarter, and back in Olean, NY I ate the best pizza I have ever tasted at Roxy’s, a place that hasn’t existed for 50 years.

Talking about that pizza reminds me that Portville is so small that people live in houses that have names. You know, like, “we live in the Hoover House.” That presumably means the original owners of the Hoover House were named Hoover, and they probably built the house back in the 1800s. But it’s some sort of prestigious thing to live in one of those mostly colonial style homes with wrap around porches.

I grew up (well, I have never grown up) in a house with a large wrap-around porch, and I’m very disappointed that the woman who lives there now does not tell her close friends that she lives in the “Mosher House.” You would think she would have more etiquette than that.

I have got to tell you that the voice of Lil Green just came pouring out of my computer speakers. The life of Lil Green makes me sad. She is singing her 1941 hit, “Do Right” that Peggy Lee and others made more famous while Lil Green faded into obscurity in black clubs in Chicago in the 1940s. Lil Green had an incredible voice, and she made the blues sound ever so much better than even Muddy Waters. Lil Green died in the Windy City in 1954. She was just 34.

Anyway, I’m sadder now than I was when I started to write about my experience with Hermosa Beach. Like I said, those were good times. Life was good. I was poor. But if I had an Iroquois and a dime for the jukebox so I would hear Buddy Holly, or some Doo Wop I was good

. And that reminds me that Earl (Speedo) Carroll, lead singer for the Cadillacs and a member of the Coasters, just belted out the Cadillacs’ big hit, “Speedo”, which is where he got his nickname. Speedo is now also gone, dying at 75.

Where was I? Oh yeah, my hometown of Portville, which really is a beautiful and very peaceful place, far removed from the crazy pace I now live. Portville would be a lovely place to live if you didn’t have to work, because there is no work there.

I had a friend texted me recently as she walked around Hermosa Beach

and as she walked Pier Avenue it all came rushing back to me. Those were happy times for a young guy like me who had no responsibilities and the world at his feet.

“Why don’t you do right, like some other men do, “wailed Lil Green. “Get out of here and get me some money too.

“Why don’t you do right?”

What a life! I was 19 and Dick was 20 and we had no cares in the world.

Hermosa Beach seemed to be the place to be in that period. On weekends the beach was full and the nightclubs on the Strand were loud. Dick and I managed to be regulars at the Vogue even though we both were underage (has the stature of limitation run out). I remember nights when the drummer for the regular jazz band would sit with us. He often would pull over an empty chair and use his drum brushes to make wonderful sounds I didn’t know existed.

On weekends we would climb into the Mercury and head to Los Angeles. Dave and Amos had rented a penthouse apartment on top of an old hotel on Wilshire Blvd. Dick would be Red Baron switching lanes back and forth on the Harbor Freeway, racing past cars that could go faster than the Mercury but drivers who had the good sense not to switch lanes as quickly and as often as the Red Baron did.

The last visit to the Penthouse is just a blur of blinking red lights, smoky haze, people I wouldn’t know by daylight, and a crescendo of music that stung my ears and sent me into a staggering blues funk.

Then one bright Sunday day as Dick stirred another strange concoction in the plastic pitcher a knock on the door was heard. I answered it and there stood a man, his wife, and daughter. Dick’s dad said too him simply, “Pack up your stuff, you are coming with us.” Within 15 minutes Dick was gone. All I know is that the family was headed back to the Middle East and my last journey with the Red Baron was completed.

Dick and I had taken in two fellows from Chicago who claimed to be ex-disk jockeys. I protested because I had a bad feeling about them – I get accurate feelings about a lot of subjects that I believe come from the “other side.” – but Dick was such a nice guy he would do anything to help, including the bad of the bad guys.

These guys, we soon found out, stole from the electronics store where they worked, and went out one night and came back with four tires they somehow found unwanted on a car someplace. And one of the guys was a big-time alcoholic (he had to have a drink in the morning to stabilize himself.)

When Dick suddenly left, I was alone with the two guys I didn’t trust or wanted around. I had saved a bunch of money and hid it to make sure my two DJs didn’t run off with it. And I immediately placed a call to Amos in Los Angeles that I would be needing a ride to the train station. I was heading back north to Ferndale. Amos couldn’t show up until the weekend, so I spent the next four days on pins and needles, hoping I was going to make it out alive.

I and my guitar rode the train to Albany, Oregon, where my brother Dave had a job, and he and I drove along the coast to Ferndale, where for the next five years I would slow down my wild and crazy life and obtain a degree from Western Washington.

The summer before my graduation I went back to Portville and walked into the Old Rose Inn. The couple who ran the place were super people. The woman had taken care of me in my bad days, often feeding and playing cribbage with me back in the kitchen. She had bet the four of us the biggest drink in the place that we would all come back from California within a year.

She lost.

So, when I walked into the place and sat down at the bar, she came over and said, “I think I owe you a drink.” The drink was supposed to be a Singapore Sling, which is a nasty thing. I told her to just give me an Iroquois, which she promptly did, placing it in front of me.

As I curled my fingers around the cold bottle I asked her, “Hey, what happened to Dick?”

All the blood drained from her face, and she stammered a response: “You don’t know?”

There was a curve just outside Duke Center that had a barn sitting right up against the road. The curve led straight to the center of Duke Center, and on nights when Dick and I used to crash at his aunt’s place we always roared around that curve, usually slick with ice and snow. But the Red Baron failed to take notice. If I protested too much for him to slow down, he would put his foot further down on the gas pedal.

One night as we roared around that curve I yelled at Dick, “If you do this one more time I’m jumping out of the car. Some night I won’t be with you, and you will crash right into that barn and be killed.”

And that is what happened in 1962. The Red Baron pressed his luck one too many times.

For the next three days, I sat in Dick and I’s favorite table in the Old Rose Inn, right by the jukebox. I drank Iroquois and plugged the jukebox with dimes, listening to our music, trying to drink the sadness from me. Occasionally, a free plate of food would be placed in front of me.

Several hours into the third day as Buddy Holly’s voice came out of the jukebox, “That’ll be the day, that’ll be the day I die”, I drank the last from my bottle of Iroquois and told myself, “Mosher, you got to stop this. You have got to move on with your life. He’s gone. There is nothing you can do.”

I rose to my feet, said goodbye to my protectors, the couple who owned the Old Rose Inn, and stumbled out the side door.

I never went back.

But I have never forgotten Dick. I see that Red Baron scarf wrapped around his neck, the ends blowing in the wind, that big grin, his hand on the stick shift, loving life to the fullest.

All three of them are gone now. Amos died from complications from diabetes and Dave, who I believe married and divorced three times, died alone except for his cats and dogs about five years later.

Me, I’m still here. I’m a little sadder. But I’m here.

I returned to Ferndale when Dick left Hermosa Beach, leased a truck from a farmer and drove in the pea harvest. One night I drove the truck into a ditch. Thanks God I was not injured and the truck survived without a scratch.

One of the pleasant surprises of working in the pea harvest is I became friends with a group of Mexicans. Each year they arrived in California for its harvest of various fruits, then tripped to Yakima Valley in eastern Washington for the apple harvest and then over to Ferndale for the pea harvest.

They were very good guys who faced their tough lives with a smile and a couple times I took several of them to Goshen, the bottle club near Sumas that stayed open on Saturday nights until 4 a.m. Washington had the Blue Laws then. You could not buy liquor after midnight Saturday until 6 a.m. Monday morning and that birthed bottle clubs.

It cost $1 to get into Goshen, which had a large dance floor. A band played there every Saturday night and customers like me would bring their own liquor purchased before midnight and you could buy alcohol mixers, chips and snacks at Goshen.

My Mexican friends behaved admirably, and we had a lot of fun.

One night I was there with some of my American buddies, and we left just as Goshen closed, headed to Bellingham to get an early breakfast. There was a four-way stop way out in the middle of nowhere that I knew about and knew that the state police would hang out there with their lights off waiting to catch the offender that failed to make a stop.

Well, tonight I failed my basic judgment. I was driving our 1950 Dodge with four other guys in the car, and plenty of beer. I turned around talking to somebody in the back seat and failed to stop at the four-way. As I traveled through the stop, I looked in the rearview mirror and saw the lights of the state trooper’s car come on.

The trooper followed me all the way to the Mount Baker highway that leads into Bellingham. As I turned on the highway, the trooper’s flashing lights came on. I pulled over and not wanting him to come to the Dodge and flash a light in the interior of the car I walked back to him.

I don’t know how straight I walked. But I gave it my best shot. He asked me for my license and as I fumbled about to get it out my wallet slipped from my hands and went flying into a ditch beside the highway. The trooper said, “Don’t worry about it, I’ll go down and get it.” I said, “No, I’ll get it” and slid down the ditch and managed to recover all the contents of the wallet that were scattered about.

After I climbed back up, the Trooper looked over my license, told me to take it carefully and let me go with a verbal warning. He followed me for a little bit, but we managed to get to Bellingham, breakfast and a story to tell.

We Olean buddies established a carpool once I registered for college at Western Washington in Bellingham. The carpool changed over the next five years, but the mainstays besides me were Pete, Ray, Moses and until he switched to mortuary school in San Francisco, Jon.

Each of us took turns for a week at a time and that went on and on for us, arriving at the school and going to the Student Union early in the mornings and sitting around hashing over various sports, and girls, until our classes started.

Our discussions over coffee were most passionate about hockey. We all could get two days a week of Hockey Night in Canada from the BBC. This was when the National Hockey League had just six teams — Toronto, Montreal, Boston, Chicago, Detroit and the New York Rangers – and we got to know all the players.

I also am still owed $10 bucks from Moses for a bet we had on the Muhammad Ali-Sonny Liston first fight. Liston was the heavyweight champion and was a 7-1 favorite when the two stepped into the ring in Miami Beach in February of 1964. Ali had yet to change his name from Cassius Clay and was yet the man who would rewrite boxing history with his charisma and boxing skills. But I was certain that his speed of hands and feet would be too much for Liston, who was considered the best puncher in the division and a menace to all.

As I predicted, Clay dominated the fight, especially the sixth round, and Liston would not come out for the seventh round. I never did get my $10 bucks from Moses and if I figure interest, he now owes me thousands. Good luck getting that.

College life was sweet. I could have stayed in college my entire life. It got me away from my home situation that wasn’t good (my father was a good person that married a woman who never thought I belonged). I felt alone and was for the most part. Brother David came to Ferndale after his first year at Syracuse. That would have been the summer of 1956. He stayed until graduating in 1960 from Western Washington. I left after graduating high school and went back to New York and went to college at Alfred Tech in the fall of 1958 and stayed until the four of us left for California in January of 1960.

Most weekends from 1958-to the winter of 1959 I spent at my sister’s house in Portville and roamed about with Lynn and Dale, drinking beer, looking for girls and trying to avoid trouble.

It was during this time frame I got banned from the Cuba Pavilion in Cuba, NY for fighting. I know once the police handcuffed me to a telephone pole while they straighten things out.